Edison closes troubled nuclear plant, but questions loom surrounding the decommissioning process

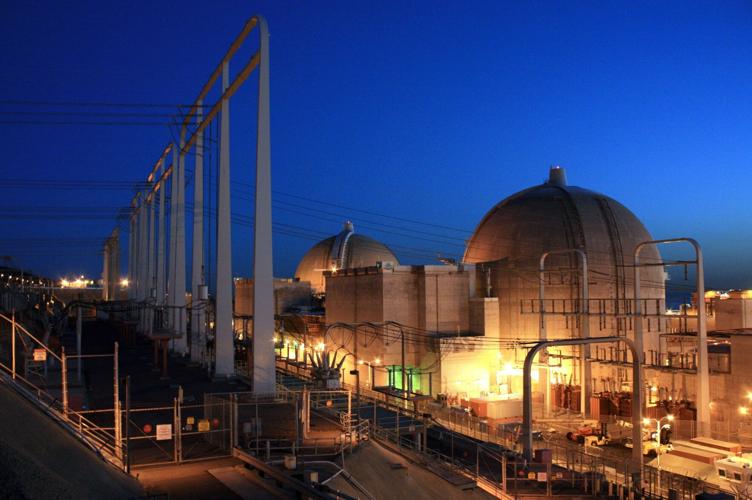

After operating since the 1960s, Southern California Edison announced in June 2013 it will close the San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station permanently. The plant must still undergo a decades-long decommissioning process. File photo

Picket Fence Media, Staff Report

Amidst billions in mounting debt and growing uncertainties surrounding a restart, Southern California Edison, the majority owner and operator of the troubled San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station, announced the plant’s permanent shutdown last week, ending a four decades long run for nuclear energy in the region.

The decision was made in light of ongoing doubt surrounding the fate of the nuclear plant since its two steam generators, Units 2 and 3, were taken offline in January 2012, after a small radiation leak was detected in the latter unit—disabled generators which until now Edison had long vowed to restart.

“SONGS has served this region for over 40 years, but we have concluded that the continuing uncertainty about when or if SONGS might return to service was not good for our customers, our investors or the need to plan for our region’s long-term electricity needs,” Ted Craver, chairman and CEO of Edison International, SCE’s parent company, said in a statement.

Edison officials announced the shutdown will result in 1,100 layoffs, reducing plant staff to 400, with the majority expected to take place over the remainder of this year.

But the plant’s 1,500-person staff will not be cut until its revised emergency preparedness and security plans, for a shutdown plant, are approved by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, Craver said. Currently, the regulatory body views the plant as operational since Unit 2 still houses nuclear fuel.

Victor Dricks, spokesman for the Nuclear Regulatory Commission Region IV, which regulates SONGS, said the NRC will continue its oversight of the plant but determination of the impact the announcement will have on existing investigations and licensing actions will have to wait until Edison submits its decommissioning plan. Edison has until the beginning of July to officially inform the NRC of its plans, and an additional two years to submit its retirement proposal.

As Edison officials take steps to layout the decommissioning plan of the active Unit 2 reactor, one fact is certain: Spent nuclear fuel will be, at least for the foreseeable future, housed at the facility.

The company reportedly has a $2.7 billion trust fund, after taxes, to handle costs associated with the closure. According to Craver, the fund, containing money collected from ratepayers each time they pay their energy bill, could cover 90 percent of Edison’s $3 billion in expected retiring expenses.

But according to Edison officials, total expenditures are anticipated at $4.1 billion, leaving more than $1 billion in funding unaccounted for.

Breaking it down

While Edison’s closure decision brings an end to nuclear power in Southern California, the seaside twin-domes along Interstate 5 will be a regional fixture, and reminder, for years to come.

The road to decommissioning isn’t a new one for Edison. After shutting down Unit 1 in 1992 to avoid a $125 million price tag for upgrades, Edison spent the next seven years removing fuel from the reactor. Work still remains for soil remediation and grading. However, the decommissioning process for Unit 1 pales in comparison to what is expected of the remaining units.

At the time Unit 1 opened in 1968, it was the largest commercial nuclear reactor in California, operating at a capacity of 436 megawatts. When fully functional, Unit 2 and Unit 3 operated at 1,070 megawatts and 1,080 megawatts, respectively, according to the California Energy Commission.

Mikael Nilsson, a chemistry and materials science professor at the University of California, Irvine, said the spent fuel rods of nuclear plants, like Unit 2 at San Onofre, will slowly be removed and initially placed underwater to dissipate radioactivity from the fission—or separating—process.

After a period of time cooling in pools, the rods—which are approximately one foot by one foot and stand one meter in height—will be placed into steel and concrete casks. While the NRC recommends that used fuel spend at least five years cooling in pools, it has in the past approved removal after just three. The industry standard for cooling is 10 years, according to the commission.

“It takes time, because you have to do it carefully,” Nilsson said. Once the spent fuel is encased in concrete, it becomes less dangerous in terms of natural disasters like seismic or tsunami events, he said.

As these spent fuel pools cannot house all the plant’s radioactive fuel at once,a lack of space and of a central national repository could keep nuclear waste at the coastal site indefinitely. The federal government defunded a plan establishing a central storage facility at Yucca Mountain in Nevada for such waste in 2010, leaving spent nuclear fuel on existing sites.

Edison’s announcement could leave two standing proposals with the NRC to restart one generator at partial capacity dead in their tracks.

Craver said that had the reactor been allowed to come back online this summer, there was a “clear cost advantage” to keeping the plant running at least until the license expired in 2022. However, as time progressed and the processes dragged on that advantage all but dissipated. Craver also noted uncertainty over whether the license could be extended in the future as playing a part in the decision.

Since the nuclear plant was taken offline early last year, Edison has spent more than $440 million for replacement power, maintenance and operational costs, according to an Edison investor report, bringing the utility’s investment in the plant to about $2.1 billion.

Craver said recovery costs in the loss of the San Onofre plant would come from four sources including ratepayers, utility insurance claims, shareholders and the manufacturer of the replacement generators, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, whose design, he said did not perform to specifications—ultimately leading to the utility’s closure decision.

But disagreements over Mitsubishi’s liability have risen.

Officials at Mitsubishi have been in negotiations with the utility over its accountability for the damage, since high vibration and other factors degraded tubes in the replacement steam generators. A letter from an Edison executive in 2004 highlighted concern over design flaws in the replacements, but aging generators were nonetheless replaced in 2009 and 2010, for $680 million.

TIMELINE: A Historical Overview of SONGS

Throughout the past 17 months—since a small radiation leak was discovered—Edison officials have been questioned about their oversight of the replacement generator’s engineering and accused of ignoring issues in order to skip a lengthy approval process. The utility has held that a more intense approval process would not have identified this kind of technical issue.

“This was such a unique phenomenon,” Craver said. While tube vibration and wear has been reported at other plants, the vibration seen at San Onofre is unlike any other in the industry, he said.

Reclaiming additional funds from Mitsubishi has been a part of Edison’s cost recovery strategy, but a statement from Mitsubishi indicated the company would not readily hand money over.

“Mitsubishi’s liability to SCE is limited by the contractual provisions to which the two parties agreed,” officials from the manufacturer said in a statement, “and includes an overall limitation of liability … as well as a preclusion of consequential damages, including the cost of replacement power.”

The steam generator manufacturer estimates its liability lies at approximately $137 million.

Before the outage, the seaside nuclear facility powered 1.4 million households in Southern California, and the plant’s two reactors provided 17 percent of all power produced by SCE. Additionally, 20 percent owner of the plant, San Diego Gas & Electric, relied on SONGS for 20 percent of its power.

With both offline permanently, the utility believes it can continue to supply power to Southern California, but the long-term planning process to replace nuclear energy will be tough. Craver said he has already spoken to Gov. Jerry Brown and Michael R. Peevey, president of the California Public Utilities Commission, about balancing the region’s energy resources and stabilizing the grid.

San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station. File photo

Since the fate of the San Onofre plant was unknown, SDG&E officials said they prepared for a summer without SONGS. Officials from the utility, which services 25 communities across San Diego and Orange counties, said barring unexpected emergencies, the 4,100-square-mile region should have adequate power supplies throughout the summer months.

In a statement assuring customers, chairman and CEO of SDG&E, Jessie J. Knight, Jr. said customers may be asked to reduce their usage on hot days, when energy demands peak. The CPUC is also working with energy customers on conservation efforts.

Rounding out ownership of the nuclear plant, the city of Riverside holds a 1.79 percent, non-operating, share. David Wright, general manager of Riverside’s public utilities department, said the city doesn’t anticipate any significant impact on rates and power supply as a result of Edison’s decision.

While the fate of the San Onofre nuclear plant is all but sealed, the state’s public utilities commission is still investigating whether ratepayers are owed refunds based on the outage of the plant, caused by the malfunctioning steam generators. At the earliest, the commission could make a decision by July.

Federal, State Officials React

Sen. Barbara Boxer (D-Calif.) and anti-nuclear activists have celebrated the announcement.

“I am greatly relieved that the San Onofre nuclear plant will be closed permanently,” Boxer said in a statement. “This nuclear plant had a defective redesign and could no longer operate as intended … and posed a danger to the eight million people living within 50 miles of the plant.”

Boxer, chairwoman of the Environment and Public Works Committee, who pushed for a heightened investigation into the San Onofre plant, added with the fate of the nuclear plant being clear, the decommissioning process needed to be done safely so it does not pose a “continuing liability for the community.”

Meanwhile, U.S. Rep. Darrell Issa (R-Calif., 49th District) called the permanent shuttering a loss for the community that places the health and safety of residents—already susceptible to failures in the power grid—at risk.

“As we face a future without SONGS, I am committed to working with government and industry leaders to build long-term plans to preserve and strengthen grid reliability,” Issa said in a statement.

Local Anti-Nuke Activists React

For anti-nuclear advocates, the news that Edison would close SONGS meant the end of a long fight, and as they gathered for a rally and press conference at the plant Friday morning, the mood was jubilant.

Gary Headrick, the leader of San Clemente Green, which has been fighting the effort to restart the plant, was elated by the news.

“It’s a huge relief and very emotional,” Headrick said. “The only thing I can compare would be the days my children were born and there’s all that anxiety and stress, you want it to come out right. And then comes the moment where the reality is they’re healthy and they’re happy.”

Gene Stone of Residents Organized for Safe Environment, said activists had won a victory with the closing of the plant, but that the fight would now move to how to deal with the spent fuel rods and other waste.

“The NRC has this program to make every nuclear power plant a waste dump for 200 years,” Stone said. “That’s totally unacceptable …we are not, in any way, going to allow this to become a nuclear waste dump.”

Jim Shilander, Brian Park, Andrea Papagianis and Andrea Swayne contributed to this report.